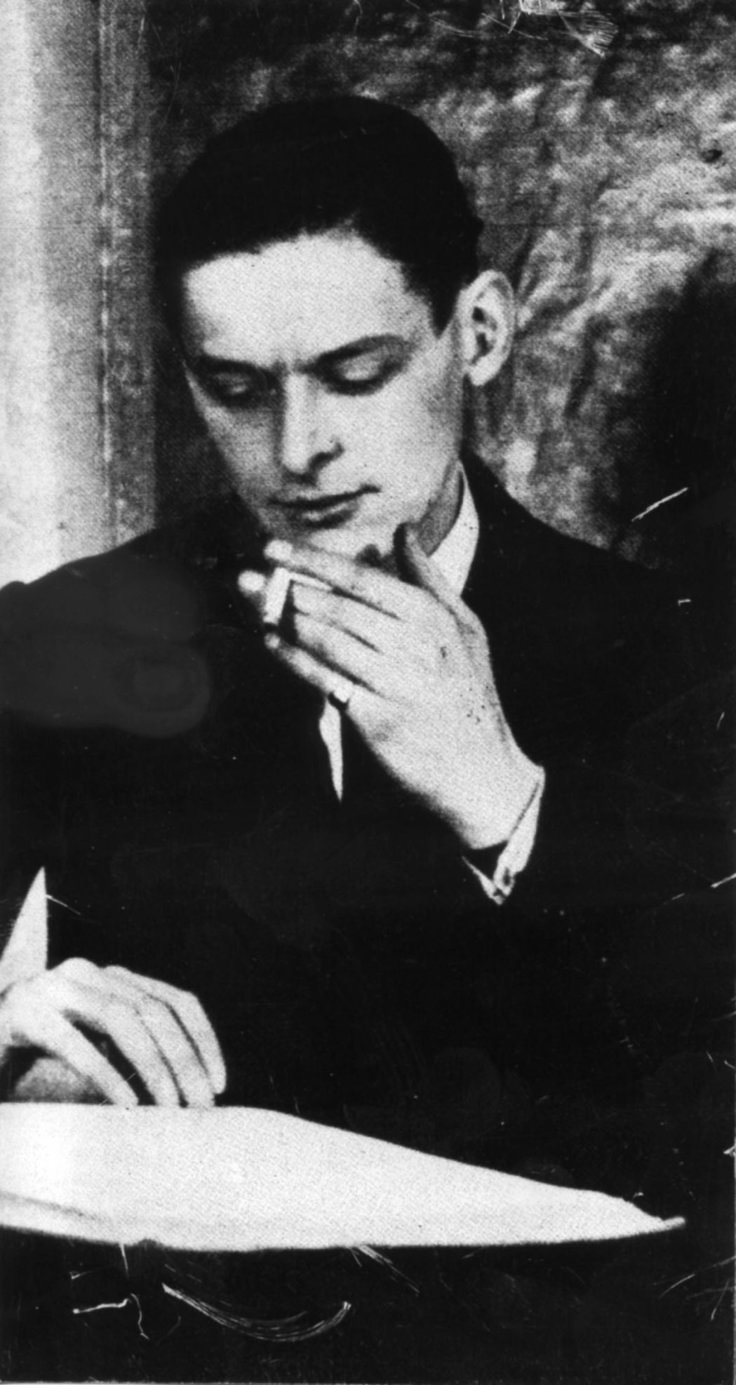

T.S. Eliot, largely known for his English-language modernist poetry, began his career as a published writer through his now well-known poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Originally published in 1917 in his book Prufrock and Other Observations, the work sought to define and criticize the modern man. This occurs throughout the poem, but can be seen in the title, alone: the name “Prufrock” is meant to be a sardonic jab at the pretentious nature of the ‘modern man’ Eliot was commenting on.

For the duration of the work, Prufrock (the speaker) attempts to deliver a love song to an unnamed erotic interest. The poem is fairly plotless, relying on features of modernist literature to provide structure to what is, in essence, a jumble of indecisive, self-deprecating thoughts that plague Prufrock’s mind. It is also important to note that, though labeled a love song, Prufrock rarely, if ever, truly focuses on his subject. In T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Eliot portrays Prufrock’s critical relationship with himself as the driving catalyst to the development of his social ineptitude towards the love interest he is implied to be speaking to, an ineptitude that carries over into the rest of his life and causes him to be estranged from his surroundings. Eliot accomplishes this largely through his modernist style, including fragmentation and stream of consciousness; he also employs anaphora, rigid diction, and extensive allusions to provide structural contrast to the poem’s disordering modernist features.

Eliot begins his exploration of the modern man’s complex relationship with the world by analyzing the relationship he has with himself. The character Eliot creates through Prufrock’s confession establishes a critical relationship with the self, which is exemplified through classic modernist techniques and provides the reader with a foundational understanding of why Prufrock might have an estranged relationship with the world around him.

One such technique that Eliot uses is inconsistencies in the stream of consciousness. Prufrock, though said to be delivering a ‘love song,’ hyperfixates on how others perceive him, allowing their opinions of him to seep into his thoughts and ideas of himself. The speaker constantly interrupts his internal monologue to contradict any idea he has of himself with that of an ominous them, in such sentiments as “My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin– / [They will say: ‘But how his arms and legs are thin!’].” Eliot’s choice to interrupt the speaker’s stream of consciousness with intrusive thoughts demonstrates two key ideas about his perception of the modern man: he has accrued insurmountable insecurities through a culmination of societal norms, and his convoluted idea of self that arises from this phenomenon directly contributes to the selfish, passionless nature of his efforts. The pervasiveness of the weight society places on the modern man is directly reflected in Prufrock’s thoughts interrupting his stream of consciousness, and Eliot’s choice to place this interruption immediately after a rare instance of Prufrock appreciating an aspect of himself highlights the idea that the modern man devalues his own opinions, opting instead to allow negative perceptions of others to overpower any hint of a positive self-image.

Eliot continues to add nuance to the idea of the modern man possessing a diminutive self-esteem by fragmenting the speaker’s narrative, arguing through this technique that the limited esteem Prufrock possesses directly contributes to the development of an extrinsic locus of control. One instance of fragmentation occurs when Prufrock reflects on his role in society, stating, “I should have been a pair of ragged claws / Scuttling across the floors of silent seas / … / We have lingered in the chambers of the sea / By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown / Till human voices wake us, and we drown.” By breaking up and distributing Prufrock’s notion of himself as a sea-dwelling bottomfeeder that drowns upon being forced to confront realities beyond the surrounding ocean, Eliot is not only able to convey the stubborn nature of the speaker’s concept of self, but also provide a perspective that paints deprecation as an excuse to live in an oasis of ignorance and be cloaked in the idea that nothing you do matters because others will always be more powerful than you. This extrinsic locus of control that Eliot assigns to the modern man is especially exemplified in the above example of fragmentation since Prufrock is awoken from his chimera of sea-girls by “human voices’‘ that eventually drown him, which suggests that the speaker views the most powerful force in his life as something other than himself. This enables him to hide behind his insecurities and be complacent in other people’s judgements and perceptions controlling his life.

Eliot goes on to claim that the modern man’s insecurities and external locus of control create a sense of apathy and self-absorption within him that prevents him from finding passion and meaning in his close relationships. This is largely accomplished through Prufrock’s forgettable relationship with the implied subject of the poem, presumably a love interest. Throughout the work, there is little indication of this interest save a few mentions of a vague ‘you.’ In fact, the primary reason the reader is aware there is a love interest at all is because the title asserts there is one. The opening stanza of the poem is arguably the speaker’s most sincere attempt at a romantic declaration: he states, “Let us go then, you and I, / When the evening is spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table.” This feeble attempt at romanticism presents a clear disconnect between the speaker and his lover. In particular, the last line employs stale diction in the comparison between the night sky and an etherized patient, which works with the function of the line as a break in the rhyme scheme to highlight the speaker’s inability to show compassion and find comfort in relationships. This inability is later revealed to be a consequence of the numbness the speaker has developed for the world after its insults became a permanent part of his consciousness.

Eliot adds complexity to the disconnect between the speaker and his implied audience, though, using anaphora to create a brief rhythm reflective of the stability the speaker finds in his beau. In a moment of internal conflict, Prufrock asks (to no particular subject), “Would it have been worth while, / To have bitten off the matter with a smile, / To have squeezed the universe into a ball / If one, settling a pillow by her head, / Should say: ‘That is not what I meant at all. / That is not it, at all.’” The repetition of ‘that is’ opening lines in this excerpt creates a fleeting rhythm that is quickly lost in subsequent lines, thus conceding that the speaker has the ability to find comfort and stability in relationships, however sparingly. Additionally, the context surrounding the anaphora implies that the speaker is contemplating a reality in which he consciously discredits the universe and the power it holds over him. The placement of this statement within anaphoric patterning provides it with a function beyond a hopeful sentiment, suggesting that it is the stability provided to the modern man through connection with others that enables him to overcome the societal pressures that force him into a self-deprecating, apathetic state.

Though Eliot briefly poses this idea, his contrast between it and the removed relationship he asserts Prufrock to have with his surroundings bolsters the idea that apathy in the modern man leads to the loss of fundamental human nature and understanding. Eliot creates this contrast through the use of allusions and symbols, likely in an effort to convey the speaker’s attempts to connect with people through mediums that have already been created as a consequence of insecurity in his own talents and the inability to properly express himself. The first instance of this technique appears in Eliot’s repeated allusion, “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.” This sequence of lines is repeated twice in the first five stanzas and calls attention to how Prufrock’s insecurities impact the way he interacts with the rest of the world, particularly women. By alluding to Michelangelo, a famed poet, Eliot incepts a negative comparison between Prufrock and Michelangelo that is demonstrative of the inferior role Prufrock chooses to take on as a member of society. Additionally, by attaching this comparison to the comments of women, Eliot asserts that the speaker feels as though he cannot create romantic relationships because he is inherently inferior to the world around him and cannot live up to expectations.

This idea is expressed again at the closing of the poem, when Prufrock describes the possible bounty to be found in releasing societal boundaries to which he lends so much credence: “Shall I part my hair behind? / Do I dare to eat a peach? / I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach. / I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each. / I do not think that they will sing to me.” The symbolic representation of wisdom and intuition through mermaids coupled with the A/B/B/B/ rhyme scheme of the surrounding lines establishes the idea that thinking for oneself and releasing the internalized need for conformity makes one more in tune with nature and provides a heightened ability to be in tune with the world. The ever-cynical Eliot, though, solidifies his critique of the modern man by highlighting his ignorance to this relationship, redirecting the speaker’s focus back to himself and how he feels the world will perceive him. This redirection highlights Eliot’s observation that the modern man prioritizes impressions and individualism rather than genuine connection with people and nature, and is either unknowing of or unwilling to learn how to create meaningful relationships with himself, others, or the world.

The portrait of a detached, complacent modern man that Eliot creates in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” through allusion, symbolism, shifting rhythm, and modernist techniques establishes his central theme that people, especially men, in modern society have grown accustomed to falling into line with what is expected of them in order to fit into the impression of a ‘good’ person. However, Eliot’s entire work can be seen as an ironic display at this notion, highlighting a disillusionment with appearances that culminates in the inability to connect with the world and the consequences this poses for humanity.

Leave a comment